During the summer of 1848 abolitionist Lucretia Mott left her home in Philadelphia and headed for upstate New York to attend a Quaker meeting and visit her pregnant sister, Martha Coffin Wright. While in the area, both Mott and Wright attended a tea party in Seneca Falls. Their friend Jane Hunt hosted the party. Invitations were also extended to Hunt’s neighbors, Mary Ann M’Clintock and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. By the end of the tea, the group was planning a meeting for women’s rights. They published a notice in local papers reporting: “a Convention to discuss the social, civil, and religions condition of women.”[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton volunteered to write an outline for their protest statement, calling it a Declaration of Sentiments. Stanton and M’Clintock, then, drafted the document, from M’Clintock’s mahogany tea table. The Declaration of Sentiments set the stage for their convening.

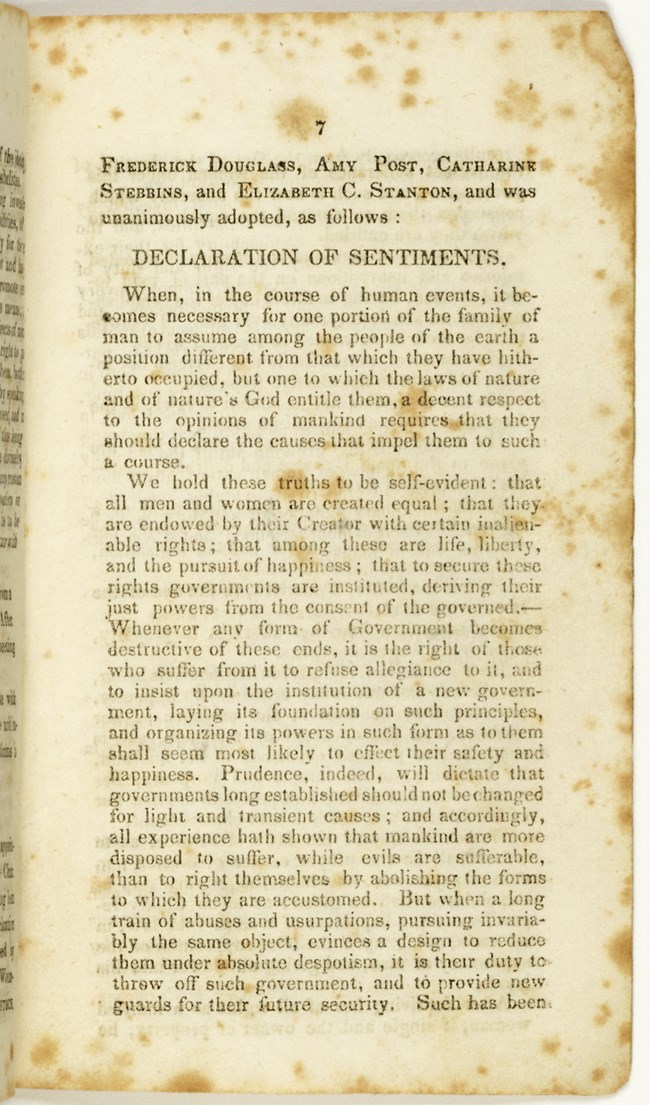

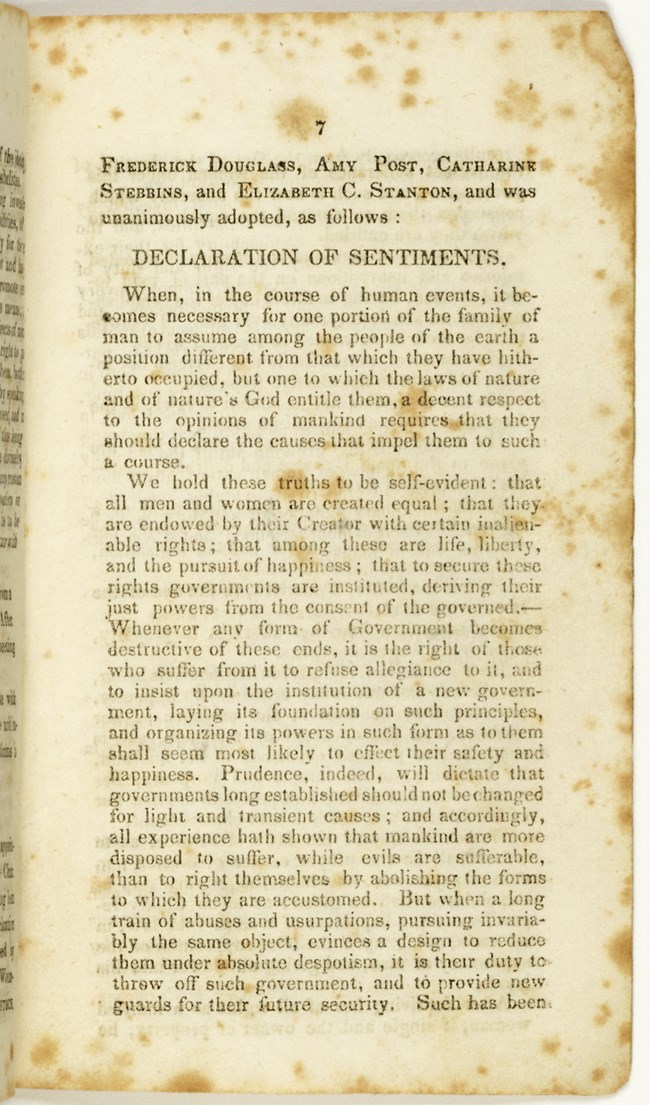

Elizabeth Cady Stanton voiced the claims of the antebellum-era conventioneers at Seneca Falls by adopting the same language of colonial revolutionaries, decades prior. Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was her template. Historian Linda Kerber perhaps best explains the significance of Stanton’s rhetorical decision, writing: “By tying the complaints of women to the most distinguished political statement the nation had made [Stanton] implied that women’s demands were no more or less radical than the American Revolution had been; that they were in fact an implicit fulfillment of the commitments already made.”[2]

The Declaration of Sentiments was a clarion call in celebration of women’s worthiness—naming their right not be subjugated. Most prominent among the critiques Stanton advanced were: women’s inferior legal status, including lack of suffrage rights (which was true except both for some local elections and in New Jersey between 1790 and 1807); economic as well as physical subordination; and limited opportunities for divorce (including lack of child custody protections). These offences were particularly ironic considering the expansive civic wartime roles women performed, including their contributions to the nation’s independence—by working as nurses and cooks, spies, and, even, fundraisers.[3]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments to dramatize the denied citizenship claims of elite women during a period when the early republic’s founding documents privileged white propertied males. The document has long been recognized for the sharp critique she made of gender inequality in the U.S. Yet, her words also obscured significant differences in the lived experiences of women across racial, class, and regional lines. For example, at the very moment Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, Native Americans were being displaced to create space for westward expansion. This does not mean they had no relationship to the women’s rights movement. Rather, matrilineal Native societies inspired women’s rights advocates who referenced them in order to claim that women in the U.S. deserved greater autonomy.[4] Additionally, African Americans in New York were but a mere generation removed from slavery. There were black women advocates of the women’s rights movement, but there is no evidence that they were invited to Seneca Falls.[5] Frederick Douglass played a prominent role in the proceedings. Making clear these distinctions creates a space to better understand both the inequalities that existed between women at the time of Stanton’s call for women’s rights and the intellectual tensions that existed in the movement during some of its earliest days. Yet, the Declaration of Sentiments as an idea created an important space for articulating the rights owed to women, one embraced by many now in a larger project of gender equality.

References:

Lori D. Ginzberg, Untidy Origins: A Story of Women’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005)

Linda K. Kerber, No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship (New York: Hill and Wang, 1999)

----“From the Declaration of Independence to the Declaration of Sentiments: The Legal Status of Women in the Early Republic, 1776-1848,” Human Rights 6, No. 2 (Winter 1977): 115.

Sally Roesch Wagner, Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists (New York: Native Voices, 2001)

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998)

Judith Wellman, Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman's Rights Convention (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004)

----“Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention,” Journal of Women's History, 3: 1 (Spring 1991), 9-37.

[1] Judith Wellman, Road to Seneca Falls (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 226; Judith Wellman, “Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention,” Journal of Women's History, 3: 1 (Spring 1991), 9-37.

[2] Linda K. Kerber, “From the Declaration of Independence to the Declaration of Sentiments: The Legal Status of Women in the Early Republic, 1776-1848,” Human Rights 6, No. 2 (Winter 1977): 115.

[3] See: Linda K. Kerber, No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship (New York: Hill and Wang, 1999).

[4] See: Lori D. Ginzberg, Untidy Origins: A Story of Women’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Sally Roesch Wagner, Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influence on Early American Feminists (New York: Native Voices, 2001).

[5] See: Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998) and Lisa Tretrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 133-135.